This article is not yet available in the language you selected

4 Risk communication

Article index

Summary

Risk communication is a powerful but often underutilized element of risk analysis. This chapter examines the role played by good risk communication in the application of the generic food safety RMF. Critical steps within the RMF at which effective communication is essential are identified, and the specific communication processes required at each stage are described. Practical aspects of communication, such as choosing appropriate goals for risk communication and how to identify and engage external stakeholders, are briefly reviewed. While ensuring good risk communication requires thoughtful planning and some commitment of resources, risk managers may find that establishing an infrastructure for communication and a climate in which communication is encouraged, expected and flows naturally, are among the most important steps they can take to achieve a successful outcome for a risk management process. This chapter does not explain “how to talk about risk”, a separate topic beyond the scope of this Guide, but readers are referred to the reference materials at the end of the chapter for advice on that subject.4.1. Introduction

Risk communication is an integral part of risk analysis and an inseparable element of the RMF. Risk communication helps to provide timely, relevant and accurate information to, and to obtain information from, members of the risk analysis team and external stakeholders, in order to improve knowledge about the nature and effects of a specific food safety risk. Successful risk communication is a prerequisite for effective risk management and risk assessment. It contributes to transparency of the risk analysis process and promotes broader understanding and acceptance of risk management decisions.Numerous reports in the international literature have described how to communicate about risks. Communicating effectively with different audiences requires considerable knowledge, skill and thoughtful planning, whether one is a scientist (a risk assessor), a government food safety official (a risk manager), a communication specialist, or a spokesperson for one of the many interested parties involved in food safety risk analysis.

This chapter examines the role of risk communication in risk analysis, and describes practical approaches for ensuring that sufficient, appropriate communication takes place at necessary points in application of the RMF. It illustrates some effective methods for fostering essential communication within the risk analysis team and for engaging stakeholders in dialogue about food-related risks and the selection of preferred risk management options. This chapter does not attempt to explain how to communicate about risks, but readers are encouraged to consult the sources listed in the references for this chapter for material on that topic.

The emphasis in this Guide is on situations where risk communication is a planned and orderly part of application of the RMF and the effective resolution of a food safety issue. However, there may be other situations, such as food safety emergencies, or technical contexts such as developing “equivalent” food standards, in which government risk managers have less opportunity and/or less need, to engage in risk communication in such a comprehensive manner. The guidance offered here should therefore be tailored as appropriate to suit specific needs on a case-by-case basis.

4.2. Understanding risk communication

Risk communication is defined as “an interactive exchange of information and opinions throughout the risk analysis process concerning risk, risk-related factors and risk perceptions among risk assessors, risk managers, consumers, industry, the academic community and other interested parties, including the explanation of risk assessment findings and the basis of risk management decisions22.”Risk communication is a powerful yet often neglected element of risk analysis. In a food safety emergency situation, effective communication between scientific experts and risk managers, as well as between these groups, other interested parties and the general public, is absolutely critical for helping people understand the risks and make informed choices. When the food safety issue is less urgent, strong, interactive communication among the participants in a risk analysis almost always improves the quality of the ultimate risk management decisions, particularly by eliciting scientific data, opinions and perspectives from a cross section of affected stakeholders. Multi-stakeholder communication throughout the process also promotes better understanding of risks and greater consensus on risk management approaches.

Given its value, why is risk communication frequently underutilized? Sometimes food safety officials are simply too overwhelmed with collecting information and trying to make decisions to engage in effective risk communication. Risk communication also can be difficult to do well. It requires specialized skills and training, to which not all food safety officials have had access. It also requires extensive planning, strategic thinking and dedication of resources to carry out. Since risk communication is the newest of the three components of risk analysis to have been conceptualized as a distinct discipline, it often is the least familiar element for risk analysis practitioners. Nevertheless, the great value that communication adds to any risk analysis justifies expanded efforts to ensure that it is an effective part of the process.

Risk communication is fundamentally a two-way process. It involves sharing information, whether between risk managers and risk assessors, or between members of the risk analysis team and external stakeholders. Risk managers sometimes see risk communication as an “outgoing” process, providing the public with clear and timely information about a food safety risk and measures to manage it; and indeed, that is one of its critical functions. But “incoming” communication is equally important. Through risk communication, decision-makers can obtain vital information, data and opinions, and solicit feedback from affected stakeholders. Such inputs can make important contributions to the basis for decisions, and by obtaining them risk managers greatly increase the likelihood that risk assessments and risk management decisions effectively and adequately address stakeholder concerns.

Everyone involved in a risk analysis is a “risk communicator” at some point in the process. Risk assessors, risk managers, and “external” participants all need risk communication skills and awareness. In this context, some food safety authorities have communication specialists on their staffs. When such a resource is available, integrating the communication function into all phases of a risk analysis at the earliest opportunity is beneficial. For example, when a risk communication specialist can be assigned to the risk assessment team, their presence heightens sensitivity to communication issues and can greatly facilitate communication about the risk assessment that occurs later in the process.

4.3. Key communication elements of food safety risk analysis

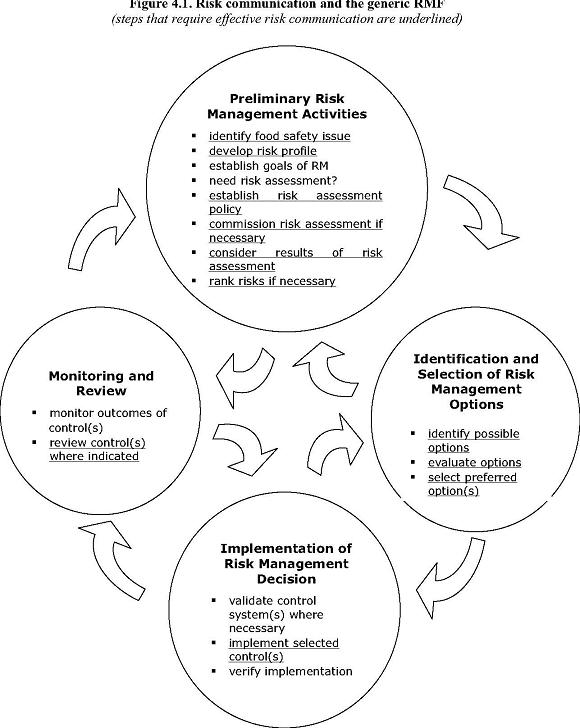

While good communication is essential throughout application of the RMF in addressing a food safety issue, effective communication is particularly critical at several key points in the process (underlined in Figure 4.1). Risk managers therefore need to establish procedures to ensure that communication of the required nature(s) occurs at the required times, and that the appropriate participants are involved in each case.4.3.1. Identifying a food safety issue

During this initial step in preliminary risk management activities, open communication among all parties with information to contribute can be invaluable for accurately defining the issue. As explained in Chapter 2, information about a particular food safety issue may be brought to risk managers’ attention by a wide range of potential sources. Risk managers then need to pursue information from other sources that might have knowledge of the specific issue, such as the industry that produces or processes the foods involved, academic experts and other affected parties as circumstances may dictate. As the definition of the issue evolves, an open process with frequent back-and-forth communication among all the participants helps to promote both an accurate definition and common perception of the issue that needs to be addressed.4.3.2. Developing a risk profile

At this step, the critical communication is primarily between risk managers, who are directing the process, and risk assessors or other scientists who are developing the risk profile. The quality of the result is likely to be enhanced if the same open and broadly representative communications network described in the previous step is maintained, and used to obtain input and feedback as the profile is developed. During this activity, the experts developing the risk profile need to establish their own communication networks with the external scientific community and industry to build up a sufficient body of scientific information.4.3.3. Establishing risk management goals

When risk managers establish risk management goals (and decide whether or not a risk assessment is feasible or necessary), communication with risk assessors and external stakeholders is essential; the risk management goals should not be established by risk managers in isolation. The government policy aspects included in the goals will vary on a case-by-case basis. The risk managers have to be comfortable that the risk management questions asked can be reasonably addressed by a risk assessment, and this assurance can come only from risk assessors. Once risk management goals for resolving a particular food safety issue have been established, they should be communicated to all interested parties.4.3.4. Developing a risk assessment policy

As described in section 3.2.4, a risk assessment policy provides essential guidelines for subjective and often value-laden scientific choices and judgements that risk assessors must make in the course of a risk assessment. The central communication process at this step involves risk assessors and risk managers. Often, face-to-face meetings are the most effective mechanism, and a considerable amount of time and effort may be required to complete the process. Usually, a number of complex issues must be considered and resolved, and even when the risk assessors and risk managers have worked with each other for some time, the different terminologies and different “cultures” of these two groups can require time and patience to agree on a risk assessment policy.

Input from external interested parties with knowledge and points of view on these policy choices is also both appropriate and valuable, at this step. Stakeholders may be invited to comment on a draft or invited to participate in a public meeting where the risk assessment policy is being considered, for example. Risk assessment policies also should be documented and accessible for review by parties who may not have taken part in developing them.

4.3.5. Commissioning a risk assessment

When risk managers form a risk assessment team and ask the risk assessors to carry out a formal risk assessment, the quality of communication at the outset often contributes significantly to the quality of the resulting risk assessment product. Here too, the communication that matters most is that between risk assessors and risk managers. The subjects to be covered include, most centrally, the questions that the assessment should try to answer, the guidance provided by the risk assessment policy, and the form of the outputs. Other practical aspects at this stage are clear and unambiguous communication of the purpose and scope of the risk assessment, and the time and resources available (including availability of scientific resources to fill data gaps that emerge).As in the step above, face-to-face meetings between the two groups is generally the most effective communication mechanism, and the discussions should be iterated until clarity is achieved by all participants. There is no single approach for ensuring effective communication between risk managers and risk assessors. At the national level, mechanisms may depend on agency structure, legislative mandates and historical practices.

Because of the need to protect the risk assessment process from the influence of “political” considerations, the role of external stakeholders in discussions between risk assessors and risk managers is generally limited; however, it is possible to obtain useful inputs in a structured manner (see next section).

4.3.6. During the conduct of a risk assessment

Traditionally, risk assessment has been a comparatively “closed” phase of risk analysis, in which risk assessors do their work largely out of the public eye. Ongoing communication with risk managers is essential here, of course, and questions the risk assessment seeks to answer may be refined or revised as information is developed. As explained in Chapter 2, Risk management, interested parties who have essential data, such as manufacturers of chemicals and food industries whose activities contribute to exposure may also be invited to share scientific information with the risk assessment team. However, in recent years, the general trend towards greater openness and transparency in risk analysis has had an impact on risk communication, encouraging more participation by external stakeholders in processes surrounding successive iterations of a risk assessment. Some national governments and international agencies have recently taken steps to open up the risk assessment process to earlier and wider participation by interested parties (Box 4.1).4.3.7. When the risk assessment is completed

Once the risk assessment has been done and the report is delivered to risk managers, another period of intense communication generally occurs (see Chapter 2, Risk management ). Risk managers need to make sure they understand the results of the risk assessment, the implications for risk management, and the associated uncertainties. The results also need to be shared with interested parties and the public, and their comments and reactions may be obtained. Since the results of a risk assessment often are complex and technical in nature, the success of communication at this stage may rest to a large extent on a history of effective communication by and among the relevant participants at appropriate earlier points in the risk analysis process.Because of its central importance as a basis for risk management decisions, the output of a risk assessment is usually published as a written report. Some examples of published risk assessments are cited in the case studies in Annexes 2 and 3. In the interests of transparency,

Box 4.1. External stakeholder participation in processes related to the conduct of food safety risk assessments at international (FAO/WHO) and national levels

|

such reports need to be complete, explicit about assumptions, data quality, uncertainties and other important attributes of the assessment, and thoroughly documented. In the interests of effective communication, they need to be written in clear, straightforward language, readily accessible to the non-specialist. Assigning a communication expert to the risk assessment team, from the outset if possible, is often helpful for meeting this latter objective.

4.3.8. Ranking risks and setting priorities

When this step is necessary (see Chapter 2), risk managers should ensure a broadly participatory process that encourages dialogue with relevant stakeholder groups. Priority judgements are inherently value-laden, and ranking risks in priority for risk assessments and risk management attention is fundamentally a political and social process, in which those stakeholder groups affected by the decisions should participate.Box 4.2 presents some examples of national processes that involved such multiparty consultation with external stakeholders. Food safety officials in various contexts have established new communication forums that bring industry, consumer representatives and government officials together to discuss problems, priorities and strategies in collegial, non-adversarial settings. Such contacts can build bridges and common understandings of issues, such as the value of risk analysis or emerging problems; they are less useful for resolving current specific disputes, although they do improve understanding of each other’s general perspectives.

4.3.9. Identifying and selecting risk management options

Decisions on issues such as risk distribution and equity, economics, cost-effectiveness and arriving at an ALOP are often the crux of risk management. Effective risk communication during this stage of the RMF is therefore fundamental to the success of the risk analysis.Box 4.2. Examples of national and regional experiences with multiparty processes for communication about broad food safety issues

|

While government food safety risk managers, based on their experience managing other food-related risks, may have a clear idea of potential risk management options, and perhaps some preliminary preferences for managing a new food safety issue, consultation at this stage may well alter these views, for instance where there is a range of possible risk management options for controlling a hazard at different points in the food production chain. The extent of this consultation will depend on the individual food safety issue. Some mechanisms for consultation with stakeholders at the national level are illustrated in Box 4.3.

Box 4.3. Some examples of processes for communication with national stakeholders on evaluation and selection of risk management options

|

Industry experts often have critical information and perspectives on possible food safety control measures, their effectiveness and their technical and economic feasibility. Consumers, who generally bear the risks from food-borne hazards, typically represented by consumer organizations and other NGOs with an interest in food safety, can also provide important insights on risk management options. This is especially likely when the options considered include information-based measures, such as consumer education campaigns or warning labels. Consulting with consumers about such measures is essential to learn what information the public wants and needs, and in what forms and media such information is most likely to be noticed and heeded.

When risk management options are being evaluated, the risk analysis process sometimes becomes an overtly political one, with different interests within a society each seeking to persuade the government to choose the risk management options they prefer. This can be a useful phase; if managed effectively, it can illuminate the competing values and trade-offs that must be weighed in choosing risk management options, and support transparent decision making. WTO members are required to implement the SPS Agreement based on transparency as a means to achieve a greater degree of clarity, predictability and information about trade rules and regulations (see Box 4.4).

In such public debates about food safety controls, industry and consumers often seem to be trying to push the government in opposite directions. While there can be genuine differences and unavoidable conflicts between what consumers want and what industry wants, the differences are sometimes less than they might seem. Food safety officials may find it useful to seek common ground by fostering direct communication

| Box 4.4. Transparency provisions in the WTO SPS Agreement Governments are required to notify other countries of any new or changed sanitary requirements which affect trade, and to set up offices (called “Enquiry Points”) to respond to requests for more information on new or existing measures. They also must open to scrutiny how they apply their food safety regulations. The systematic communication of information and exchange of experiences among the WTO’s member governments provides a better basis for national standards. Such increased transparency also protects the interests of consumers, as well as of trading partners, from hidden protectionism through unnecessary technical requirements. A special Committee has been established within the WTO as a forum for the exchange of information among member governments on all aspects related to the implementation of the SPS Agreement. The SPS Committee reviews compliance with the agreement, discusses matters with potential trade impacts, and maintains close co-operation with the appropriate technical organizations. In a trade dispute regarding a sanitary or phytosanitary measure, the normal WTO dispute settlement procedures are used, and advice from appropriate scientific experts can be sought. |

between industry and consumer representatives, in addition to the ongoing communication that each sector maintains with the government agencies themselves (see Box 4.2).

4.3.10. Implementation

To ensure that a chosen risk management option is implemented effectively, government risk managers often need to work closely, in an ongoing process, with those upon whom the burden of implementation falls. When implementation is carried out primarily by industry, government generally works with the industry to develop an agreed plan for putting food safety controls into effect, then monitors progress and compliance through the inspection, verification and audit process. When risk management options include consumer information, outreach programmes are often required, for example to enlist health care providers in disseminating the information.Surveys, focus groups and other mechanisms also can be pursued to measure how effectively consumers are receiving and following the government’s advice. While the emphasis at this stage is on “outgoing” communication, the government needs to explain to those involved what is expected of them, mechanisms should be built into the process to collect feedback and information about successes or failures of implementation efforts.

4.3.11. Monitoring and review

At this stage, risk managers need to arrange for the collection of relevant data needed to evaluate whether the implemented control measures are having the intended effects. While risk managers take the lead in developing formal criteria and systems for monitoring, other inputs may enhance this determination. Parties other than those designated as responsible for monitoring and review activities may be consulted or may bring information to the attention of the authorities at this stage as well. Risk managers sometimes use a formal risk communication process to decide whether new initiatives are needed to further control risks.Communication with public health authorities that are not integrated in food safety authorities is especially important during this step. The importance of integrating scientific information from all aspects of monitoring hazards throughout the food chain, risk assessments, and human health surveillance data (including epidemiological studies) is emphasized throughout this Guide.

4.4. Some practical aspects of risk communication

While the advantages of effective risk communication are obvious, communication does not occur automatically and it has not always been easy to achieve. Communication elements of a risk analysis need to be well organized and planned, just as risk assessment and risk management elements are. When resources permit, governments may include specialists in conducting or managing communication aspects of food safety risk analysis among their staff. Whether managing risk communication falls to a specialist or to someone with more general responsibilities, a number of practical questions are inevitably encountered. This section examines some of those questions and suggests some workable approaches for answering them in the national context.4.4.1. Goals of communication

When planning for communication, an essential first step is to determine what the goal is. For instance, at each of the steps examined in section 4.3 above, communication has a somewhat different focus. Those planning communication programmes need to establish: i) what the subject of the communication is (for example, risk assessment policy, understanding outputs of a risk assessment, identifying risk management options); ii) who needs to participate, both generically (i.e. risk assessors, affected industry) and specifically (i.e. which individuals); and iii) when during the risk analysis process each kind of communication should take place. The answer to this last question can be “often”; that is, some communication processes do not occur once, but may be reiterated, or ongoing, during large portions of or throughout application of the entire RMF.Box 4.5. Some pitfalls to avoid: What risk communication is not good for

|

It is also important to avoid choosing inappropriate risk communication goals (see Box 4.5). Communication efforts undertaken without sufficient care as to what they are intended to accomplish often turn out to be counterproductive.

4.4.2. Communication strategies

A great many specific strategies for effective risk communication have been developed for use in various contexts, including food safety, and in different cultures. Some basic components of a risk communication strategy in the context of food safety risk analysis are summarized in Box 4.6. An in-depth review of such strategies and principles is beyond the scope of this Guide; readers are encouraged to consult the references at the end of this chapter for more detail.Box 4.6. Strategies for effective communication with external stakeholders during a food safety risk analysis

|

4.4.3. Identifying “stakeholders”

While risk managers may agree with the general goal of inviting affected stakeholders to participate at appropriate points in application of a RMF, it is not always a simple matter to know specifically who those parties are, or to get them engaged in a particular risk analysis process. Often, affected stakeholder groups are known to risk managers from the outset, or identify themselves and seek to participate early in the process. Sometimes, however, some affected stakeholders may be unaware of the need for or the opportunity to participate, and authorities may need to reach out to them. Most countries have laws and policies about how and when stakeholders can participate in public decision-making processes. Risk managers can work within such frameworks to optimize participation. Box 4.7 lists some sectors of society who may have a stake in a given food safety risk analysis. When risk managers seek to identify appropriate stakeholders, the criteria in Box 4.8 may be useful.Box 4.7. Examples of potential stakeholders in a particular food safety risk analysis

|

Mechanisms have been established in many countries for engaging stakeholders in food safety decision making at the national level in a general, ongoing way. Participation by interested parties in such broader activities may increase their awareness of new food safety issues, and builds the government’s familiarity with interested sectors of the society. For example, some countries have set up a national food safety advisory committee, a national Codex committee, a network of industry and civil-society contacts who wish to take part in Codex-related activities, and similar organizations. To the extent that such networks exist, they can be used to ensure appropriate risk communication with relevant stakeholder groups. Where such mechanisms have not yet been established, the benefits they offer in terms of supporting participation of affected interested parties in risk analysis is only one of many advantages national food authorities may gain by creating them.

Box 4.8. Criteria for identifying potential stakeholders to participate in a given food safety risk analysis

|

Once stakeholders are identified, their role in a given risk analysis needs to be defined. While potentially valuable inputs from stakeholders in different sectors can occur at most stages of the generic risk management process, constraints may exist in specific cases. For example, in a situation that demands urgent action, time for consultation may be very limited. In some cases stakeholder participation may not have much genuine influence on the decision; if the decision is not really negotiable, stakeholders should be informed so that they do not feel that they are wasting their time.

4.4.4. Methods and media for communication

Depending on the nature of the food safety issue, the number and nature of the stakeholder groups involved, and the social context, a great many alternatives may be appropriate for conveying and receiving information at various points in application of the RMF. Box 4.9 lists some of the more widely applicable options.| Box 4.9. Some tactics for engaging stakeholders in a food safety risk analysis | |

|

Meeting techniques

|

Non-meeting techniques

|

While there will probably always be a need for detailed written documents, scientific reports and official government analyses of food safety issues and decisions, effective communication often requires additional approaches. Some of the familiar mechanisms, such as meetings, briefings and workshops, can be tailored so as to attract participation by different stakeholders whose involvement is desired. For instance, a workshop on scientific and economic aspects of the food safety controls relevant to the issue under consideration would be likely to attract robust food industry participation, while a panel discussion on the latest advances in risk analysis methodologies should appeal to many academic experts, as well as to other stakeholders.

Some of the “non-meeting” approaches can be quite creative. For example, a number of years ago government officials and consumer organizations in Trinidad and Tobago organized a calypso contest to engage community members in promoting awareness of food safety and a variety of other consumer issues. Especially when the goal is to inform and engage the public, messages intended for specific audiences need to be presented in media the audiences pay attention to, and efforts to gather information need to be carried out in a place and in a manner that will encourage those with the desired information to take part in the process.

Which of these approaches, or perhaps others, may be most appropriate will depend on the issue, the type and nature of stakeholder groups, and the context. In general, large public meetings are not especially effective for eliciting the transparent dialogue that risk communication seeks to achieve. When involving members of the general public is one of the objectives, internet discussion boards and chat rooms and call-in television and radio programmes enable members of the general public to share views and concerns and to obtain information from experts and decision-makers.

4.5. Suggestions for further reading

FAO/WHO. 1999. The application of risk communication to food standards and safety matters. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation. Rome, Italy. 2–6 February 1998. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper No. 70 (available at: http://www.fao.org/DOCREP/005/X1271E/X1271E00.htm#TOC).Fischoff, B. 1995. Risk perception and communication unplugged: Twenty years of process. Risk Analysis, 15: 137-145.

Joint Institute for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. Web site of the Food Safety Risk Analysis Clearinghouse. A joint project between the University of Maryland and the United States Food and Drug Administration. Collection of resources related to food safety risk communication (available at: http://www.foodrisk.org/risk_communication.cfm).

National Research Council. 1989. Improving Risk Communication. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

National Research Council. 1996. Understanding Risk: Informing Decisions in a Democratic Society. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Sandman, P.M. 1994. Risk communication. In Encyclopaedia of the Environment. Eblen, R.A. & Eblen, W.R. (eds.). 1994. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, pp. 620-623.

Slovic, P. 2000. The perception of risk. Earthscan, London.

University of Maryland. Food safety risk communication primer. Available on the web site of the Joint Institute for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (see above).

WTO. 2002. Operating the SPS Enquiry Point. Chapter 4 in How to Apply the Transparency Provisions of the SPS Agreement. A handbook. WTO Secretariat (available at: http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/sps_e/spshand_e.pdf).

Notes:

22

Definition from the Codex Alimentarius Commission. Procedural Manual, 15th Edition.

Source: FAO

back to top

back to top

companias

companias